We were heading out the door when I realized my mother thought our dryer was trying to kill us.

“Turn the dryer off,” she’d told me.

“Why?” 10-year-old me asked.

“I don’t want it to catch on fire while we’re away.”

Looking back, 26-year-old me wonders why it would’ve been preferable for the house to burn down with us there instead of away, but 10-year-old me just nodded and turned off the dryer. The clothes remained damp until our return. Just like every other time we had to go somewhere mid-cycle.

Mom, now almost a decade deceased, had numerous such obsessions. Another one related to the dryer: She emptied the lint filter as if lint was about to replace the dollar as America’s currency. “The lint will catch fire if you let too much build up,” she’d say—or shout, if I was in another room—after seemingly every load.

I left for college convinced dryers were pyromaniacal death machines, so I was shocked during my freshman year to find people didn’t always empty lint filters. Sometimes I’d open a communal dryer and find six or seven layers of lint from six or seven cavalier undergrads. You fools, I thought each time I cleaned a choked filter. You’ll burn the college down, and then we’ll have to apply somewhere else.

Another of Mom’s fears was based not on fire but water. No matter how much of her I come to forget, I will never be able to throw a plastic six-pack ring away without hearing her in my head: Cut the rings apart or you’ll strangle a fish! And every time I hear that, I obey and take the rings apart. But instead of cutting with scissors I tear with my hands, because I know she’d find the brutality scold-worthy—You’ll hurt your fingers!—and I like that.

—

As long as I knew her she bought no vehicles but Subarus, largely because of their reputation as safe. But she still found ways to make driving seem extremely dangerous. Sometimes, when I was old enough to ride in the front but still short enough to fold my legs up, I’d thump a foot onto the passenger-side dashboard. “Don’t do that or you’ll set the airbag off!” always came Mom’s warning. If Subaru airbags actually worked that way, I later realized, then Subarus would be terribly unsafe.

Paradoxically, Mom still viewed Subarus as paragons of safety. While beaming over her first Subaru Forester, a low-slung SUV, she told me, “It’s good it sits so low to the ground because the bigger SUVs roll over all the time.” For a stretch after that, I flinched every time a Chevy Suburban or Ford Expedition passed us on the highway, certain the larger vehicle was about to topple over and crush us.

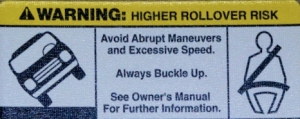

As with the six-pack rings, I’m still trying to rebel. Earlier this year, I bought a newer, taller Forester—they’ve gotten a bit bigger with each redesign—and smirked when I saw this label on the visor:

It made me like the vehicle more.

—

Along with Mom’s affinity for Subarus, I’ve inherited much of her anxiety. One manifestation: Every time I leave somewhere and plan to be gone for more than a day, I need to do several laps around the place to make sure everything’s turned off, I have all my belongings, and no animals are being strangled by six-pack rings in the corner. If I’m traveling with someone, they eventually resign themselves to going outside, sitting in my Subaru, and hoping it doesn’t roll over while they wait.

Once, while my girlfriend, Rosie, was helping me close up a house that was going to sit empty for a few days, she asked if it was OK to leave a package of hot dog buns on the kitchen counter. “No,” I said. My tone befitted a request to shoot me in the thigh: “That’d bring mice!” Mom’s words in Dad’s voice.

Rosie responded by heading for the Subaru. I joined her half an hour later, laps complete.

—

Despite the contrary evidence, Mom’s anxieties fueled her best qualities. Her concern for animals—Cut the rings apart!—manifested itself in hundreds of hours spent volunteering for the local animal shelter. Though her car- and dryer-related fears were tough to take seriously, they were borne from her trying to keep her family safe. And she did the same for her pals; one of her lifelong friends, Sharon, told me, “She was the caretaker and worrier of our group. Always pointing out the danger.” She turned her worries into her best trait: bottomless caring.

Likewise, I benefit from this neuroticism. I’m an editor by trade, and while compulsively triple-checking a document out of fear I’ve missed something is stressful enough to twist my intestines, it’s rewarding when it turns up a would-be $20,000 mistake.

I learned about taxes, investments, and retirement planning years before most of my peers, because in my early 20s I became convinced I’d be a bankrupt, accidental tax cheat by 30 if I didn’t wise up.

And I picked up my now-favorite activity—improv comedy—not because I wanted to go on stage and be funny, but because at 25 I got an obsessively nagging thought that I’d die miserable by 50 if I kept pounding beer and watching hours of Netflix every night. It’s tough to enjoy Trailer Park Boys with that anxious snake in your head, so I signed up for an improv class to get myself out more. A year later, it’s what I enjoy doing most.

Our anxiety—and I say our assuming Mom’s experience felt similar to mine—can’t be called a double-edged sword, because a double-edged sword would still have a hilt, and thus an obvious way to keep it from hurting its wielder. (I’m not sure if dwelling on cliches counts as anxiety or just pedantic introspection.)

Instead, our anxiety resembles the shrapnel embedded in Iron Man’s chest, poised to destroy his heart: It could’ve taken him out, but instead spurred him to make an armored suit and start shooting lasers at his problems.

I often wish neither of us had shrapnel, Mom, but thanks for passing on enough armor to deal with it.